“I would not exchange my small, dirty cell for a king’s palace if I was required to give up even a small part of my faith,” he writes. But he seeks God with fierce devotion and accepts the political consequences of his faith, which boils down to this: he withholds his cooperation from the warmaking state and offers his life for God’s reign of peace. More, his writings reveal a man committed to God’s peace even as the church regarded Franz as wayward and complied with Hitler’s wars.įranz reflects his culture and times, from his German Austrian character to his pre-Vatican II theology and spirituality, some of it a bit musty by our standards. Franz’s writings reveal a person struggling with the ordinariness of life amid extraordinary times - the extraordinariness heightened by the demands of the Gospel. ? How could so unimportant a person dare to have such important convictions?”įinally, we know the answers. Jim Forest, in his introduction writes, that “Franz Jagerstatter was one of the least likely persons to question the justifications of war being announced daily by those in charge or to say no to the demands of his government. And he was ready to suffer and die for the sake of his personal integrity and his vocation. He was acutely aware of human sinfulness and divine compassion. He attained an insightful analysis of the cultural, political, religious and social dynamics of his day - an analysis that generated his predictions about life after the war. For example, he felt an exceptional intimacy with God. He exhibited many of the personal traits of the Old Testament prophets such as Elijah, Amos and Jeremiah. Krieg writes that Franz “was not only a martyr and a saint but also a prophet, in the biblical sense.”

Radegund, Austria, where Franz is buried. Franziska keeps the originals at their home in St.

Most of his last writings, in particularly, were written clandestinely and in chains, to be delivered to Franziska after his execution. But now, in this volume, edited by Erna Putz with commentary by Robert Krieg, we have all that Jagerstatter wrote. It included excerpts from some of Jagerstatter’s letters and prison essays. Zahn's book In Solitary Witness came out in 1964. A year and a half ago, he was beatified during a Mass in Linz, Austria, with his children present along with his dear widow Franziska, now 96.įor decades Jagerstatter’s story languished. On August 9, 1943, for refusing to take “the military oath of unconditional obedience to Hitler,” Franz Jagerstatter was beheaded. And we learn a thing or two about growing in sanctity and how we might resist war and practice Christ’s peace. Through his intimate letters and powerful reflections on faith, church and death, we enter the mind of a contemporary saint and martyr.

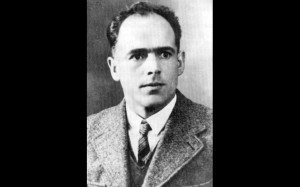

He was beatified on Octoand his feast day is May 21.A few weeks ago, Orbis Books published Franz Jagerstatter: Letters and Writings from Prison, the first complete collection of his writings in English. In 2007 Pope Benedict XVI declared Franz Jagerstatter a martyr. He was subsequently tried and executed by guillotine on August 9 at age 36. Called to active duty in 1943 he announced his conscientious objection. He became convinced that participation in the war was a serious sin. In 1938 he was the only citizen to vote against the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Germany. He and his wife had three daughters.Īlthough not involved with any political organization, Franz became increasingly anti-Nazi. His marriage to a deeply religious woman in 1936 settled him down and encouraged his growth in the faith. He gained a reputation for wildness while growing up-he was the first in his village to own a motorcycle-and fathered a daughter out of wedlock. The Second World War produced several saints one of them was Blessed Franz Jagerstatter, husband, father and Austrian conscientious objector.įranz was born on in Upper Austria.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)